“The Future is Degrowth: A Guide to A World Beyond Capitalism” is an amazing new book enriching the degrowth discourse. Written by Matthias Schmelzer, Aaron Vansintjan and Andrea Vetter, it discusses why and how to break free from the capitalist economic system. Jana talked to Aaron, R&D member and co-author of the book, about theories of change, about feminist and decolonial origins and about what it is like writing a book during a worldwide pandemic.

Aaron, thank you so much for taking the time to answer my questions. Can you summarise in a few sentences what this book is about? What new argument does it contribute to the degrowth discourse, compared to the books of Giorgos Kallis, Jason Hickel and Timothée Parrique for example?

Aaron: The Future Is Degrowth, like the other works you mention, seeks to introduce degrowth to new audiences. However, it begins from an explicitly leftist—that is, an anti-capitalist, feminist, and anti-racist—position, and argues for degrowth from that perspective. This allowed us to engage with topics like the Green New Deal, ecomodernism, and social movement strategy. It also allowed us to be in conversation with degrowth itself, seeking to push it on some debates that we felt were necessary, such as the problems of far-right environmentalism, imperialism, and capitalist hegemony.

In her review of the book, Silvia Federici congratulates you for having written “a book that powerfully challenges any reductive views of degrowth”. You manage to synthesise many different concepts, and touch on climate justice, animal ethics, theories of property and value and many more, all in one book. Does that make the book directed to an audience with a rather academic background? Or would you also recommend the book to people that have never engaged with degrowth?

Aaron: The book is essentially a textbook on degrowth. In that sense it is introductory. But if you try to lay out these quite in-depth debates adequately you will have to get quite precise with language. This means that the book can sometimes feel heavily laden with many concepts and terms that a lot of readers will not be familiar with. We have tried our best to define each essential term when we use it, while not sacrificing precision.

I think this has paid off. The book seems to be really popular in reading groups and university-level classes. I have had very good feedback from teachers, who have enjoyed working with the book with their students. I heard someone describe it as Degrowth 201—a bit advanced beyond high school or first-year university level, but still accessible. Because of its structure, it is also very possible for students to be assigned single chapters, for example, the chapter on the history of growth, or the one on degrowth strategy. The chapters actually stand by themselves pretty well, so it is still useful for those who don’t have time to read a whole book. We insisted on an index so that people can easily skip to the topics that interest them.

The book will also be relevant for those interested in topics beyond degrowth. As you say we do (very briefly) discuss non-human ethics and so on. There are some important sections, for example, on queer ecology, ecological humanism, ecomodernism, and technology. This is because we argue that degrowth’s strength is precisely in its holistic, intersectional approach to complex issues. In that sense it may be valuable for anyone new to environmental thought, or anyone trying to work toward social change.

Timothée Parrique in his review acknowledges the great work you have done recognizing the feminist current within degrowth. I personally appreciate this visualisation of feminist theorists and practitioners very much, as in the degrowth discourse it sometimes lacks explicit engagement. Don’t you think that there is also a decolonial current of degrowth that could potentially be acknowledged and delved into more?

Aaron: We are standing on the shoulders of feminist giants! As you say we felt it was imperative to highlight, and in some ways recover, the centrality of feminist thought to degrowth. Some of the greatest thinkers of our time, and degrowth’s greatest influences, are eco-feminist and queer theorists.

The same must be said of decolonial movements and thought. In fact degrowth has its roots in the anti-colonial and alter-globalisation movements of the 1980s and 1990s, which were responding to structural adjustment (i.e. immiserating growth) programs imposed by the West on the Third World. Degrowth is, and must continue to be, an ally to Global South struggles, such as Indigenous, peasant, anti-imperial, and worker movements. I am seeing a lot of work from the Global South drawing from degrowth and its critique of the growth hegemony which remains really relevant in Global South countries, who are bound by neo-colonial debt and whose social movements are trying to provide alternatives to the hegemonic development model based on growth. Likewise, degrowth continues to have a lot to learn from these movements, as well as movements for migrant justice, Black liberation and Indigenous self-determination in the Global North.

Because of all this, we dedicate a significant portion of the book to the decolonial, internationalist current. It can always be highlighted more and there is more to be done here, more alliances to be made.

From a personal research interest on the topic of degrowth and strategy, I really liked the chapter on “Making degrowth real”. While interstitial and symbiotic approaches are usually delved into in the discussion, you also include ruptural strategies of civil disobedience, that are often dismissed by other authors. Why did you choose to emphasise them?

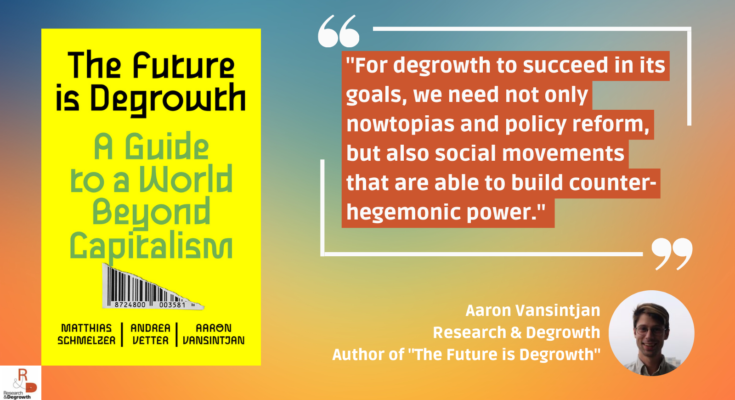

Aaron: I’m glad you liked that chapter, and I hope it was useful. For degrowth to succeed in its goals, we need not only nowtopias and policy reform, but also social movements that are able to build counter-hegemonic power. We refer to this as “dual power”, which is where democratic and autonomous organisations such as unions, assemblies, and councils build their own power which could either challenge the state or hold it accountable. Popular education is paramount to this effort as dismantling the growth hegemony will also require consciousness-building, imagination, and desire for change. Such movements can interact symbiotically with reformist strategies (e.g. policy reforms, political parties) and interstitial strategies that operate “in the cracks” of capitalism. For this reason we felt it was necessary to centre ruptural strategies in our book.

That said, some of the reviews of the book have pointed to the fact that even our discussion of ruptural strategies under-theorises, and in some ways neglects, a theory of change. We state quite clearly from the outset that we are not in the business of blueprints for utopia: these usually go wrong anyway, and often end up out of touch with an ever-shifting political landscape. But some readers seemed to want more discussion of, for example, which agent of change should we prioritise (e.g. workers, municipalities, peasant movements, etc.), what a successful strategy vis-a-vis the state might look like, or how degrowth would deal with, say, capital flight when services are decommodified. When I give talks about the book, these are some of the questions that the discussion tends to gravitate towards. There is a lot more work to be done here and there continues to be a need for degrowth to sharpen its understanding of how social movements can navigate political realities, and what concrete role degrowth proponents may have in influencing the direction of history.

In the last chapter, you identify gaps in the literature that degrowth should further involve with. One of them is democratic economic planning, which a very recent paper by Matthias Schmelzer et al. took on. Do you have future plans to engage with other of the research gaps you identified, e.g. class and race, geopolitics and imperialism or degrowth and digitalisation?

Aaron: I’m particularly interested in the topics of geopolitics and imperialism. My own research focuses on the role of financialization and speculation in both maintaining global neoliberalism and the potential this offers for international solidarity—for example through the struggle over land, which connects, for example, urban residents dealing with the massive power of the real estate sector, slum dwellers, peasants whose land is being enclosed through the speculation on farmland, and Indigenous struggles. Given that 60% of global capital is invested in real estate, this reality offers us unprecedented power to connect our struggles across borders, class, and race.

I am also increasingly focused on storytelling and science fiction and its role in imagining and creating the desire for a different future. We badly need a new imaginary, one which does not take technology or capital as the agent of history, but rather working people and the ecologies that they foster. And, more simply, I’ve personally felt the need for injecting some play and whimsy into my life. If I can’t dance, it’s not my revolution!

Last but not least, a more personal question: How did you like the process of writing this book? Would you at some point like to produce a sequel, a volume two of the book?

Aaron: I really enjoyed working with Andrea and Matthias, all things considered. We started working together in March 2020. Basically right when the pandemic happened. In a way the process of writing and editing kept me grounded through those challenging first months. We included quite a bit of discussion about the effects of the pandemic in the book, which certainly helped me process what was going on in my life, and our regular meetings over zoom became a space to share how things were affecting us. We still have never met each other in person. Despite that, writing a book together is a special process and you can start to feel quite connected, despite the distance.

We haven’t discussed a sequel. I could see us updating the book for a new edition in some years, or perhaps even creating a shorter, more accessible version. My preference would be to see what happens organically—what is needed in the world? We are now keeping busy with speaking engagements and managing the translations that are coming out. It turns out writing a book is hard, but honestly the business of promoting a book once it’s out feels even harder. It’s a kind of work I’m not used to. Once that dies down, I do hope that we can find ways to continue working together, in whatever format.

If you haven’t read the book yet, get your copy here or in your local bookstore. And let us know in the comments how you liked it!