What makes cities thrive? From 'Creative Cities’ to Cultural Municipalism

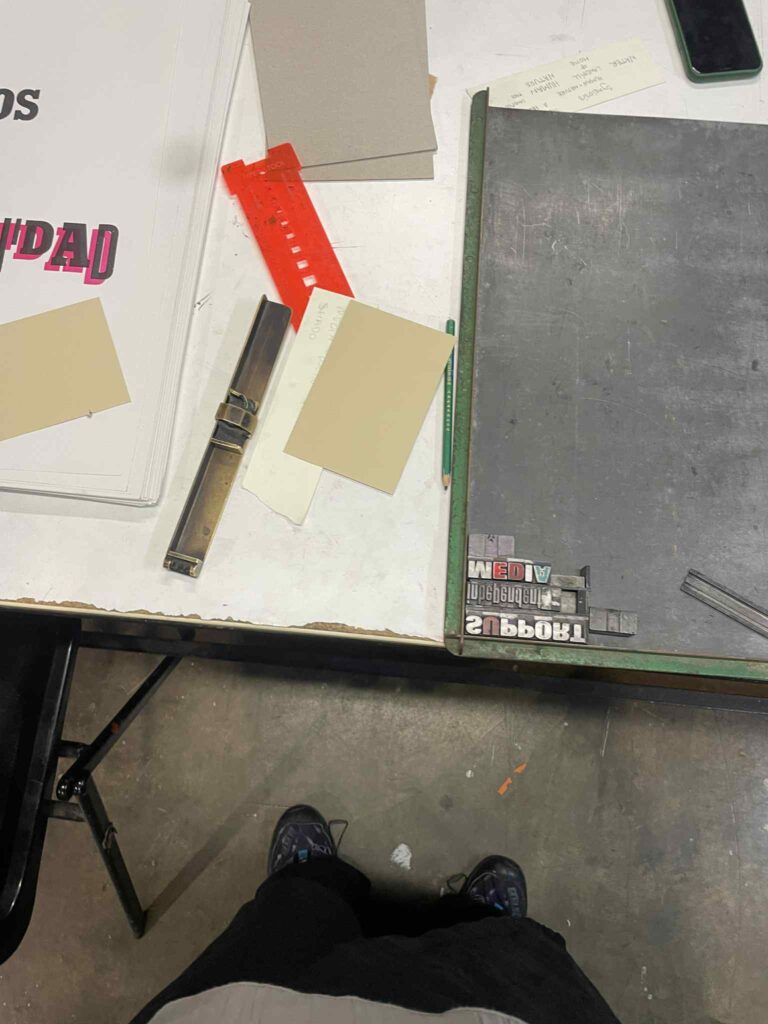

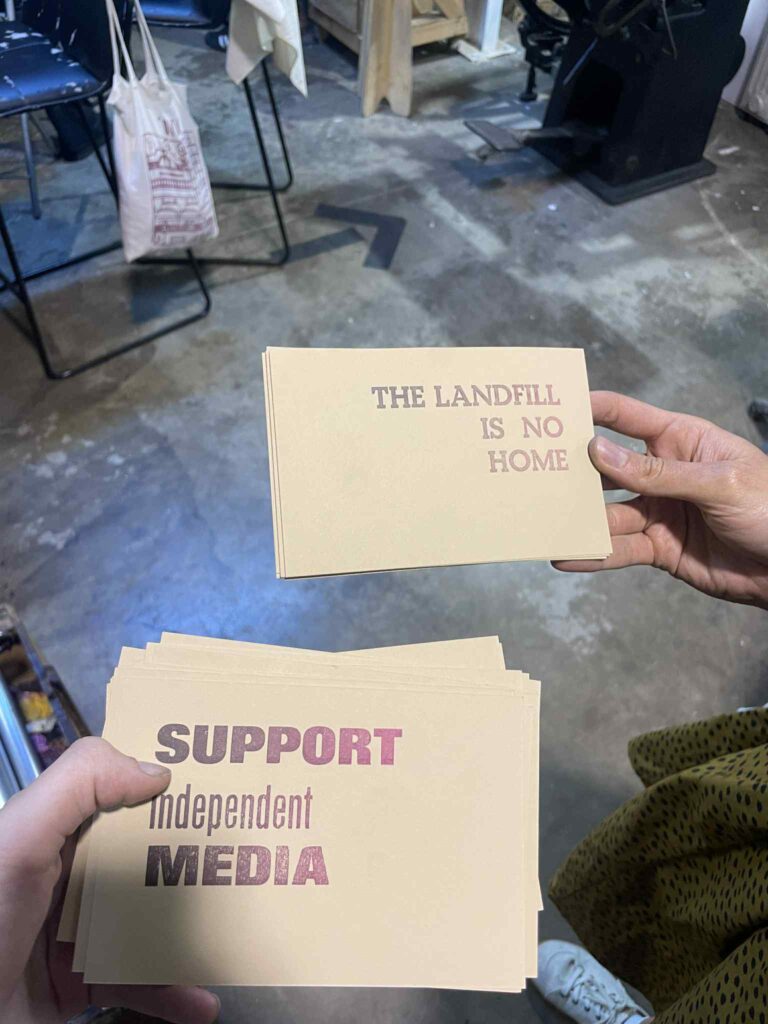

“The space is free from the council, and the collective generates a little bit of income by working with movements to create posters for them, and then we keep some of them to sell.”

I’m at La Imprempta Col·lectiva, a leftist slow printing press in Can Batlló, Barcelona, receiving a tour from Carmela. The warehouse studio is lined with cluttered shelves and long washing lines of bold prints left to dry hang low – documenting protests, movements, calls to action from local and international resistance movements. Ancient printing machines are crammed between tables littered with ink pots. Members of the collective chat over beers and smoke roll-ups, plotting designs commissioned by local leftist groups. Their letterpress printing requires precision: one small mistake means re-starting from scratch.

Anyone can attend their Thursday afternoon sessions, where participants learn how to use the printing press and make prints for whichever leftist collective is working with them that week. Even I, with my broken Spanish and nonexistent Catalan, am welcomed with a hug and a beer.

Since I moved to Barcelona four months ago, I have been thinking about what makes cities thrive. After ten years in London, why does Barcelona feel so much more vibrant? For sure, it’s the walkability, the sunshine, and new city bias. But it’s also walking into a warehouse just three weeks after moving here, for free, and immediately connecting to something. Carmela explains the posters they’re creating for a trans-feminist collective organising a set of workshops soon. The world opens up easily.

Personal photos from my afternoon with Impremta Col·lectiva

London vs. Barcelona

In London, the walls are closing in. Skyrocketing rents, gentrification, sterile apartment blocks replacing community centres. To express my creativity, I resorted to taking an expensive painting course – 45 minutes away by bus.

In Culture is Not an Industry: Reclaiming Art and Culture for the Common, Justin O’Connor argues effective cultural infrastructure is invisible, subtly enhancing your city experience: like meandering past an independent bookshop or stopping by a little music venue with cheap pints where local bands play their first gig (2024). But when the cultural ecosystem falters, these small spaces disappear first.

The UK’s cultural scene is coughing up blood. Independent venues who made it through the pandemic had no financial reserves when the energy crisis hit. In my roaming around Barcelona, I can’t help but ask: how does a space like this – La Impremta Col·lectiva – exist? Barcelona is no stranger to gentrification, it makes London’s housing crisis seem like a walk in the park (and I don’t say this lightly). Yet this print shop embodies what makes cities good to live in: accessible arts and culture, connecting with new people, feeling part of something bigger. It is a space of enjoyment and resistance, a crossroads where movements, artists and the city converge.

How did I walk in here just weeks after moving?

La Impremta Col·lectiva operates rent-free in Can Batlló, a self-managed social and cultural space in an old textile factory. It is precisely Can Batlló’s relationship with the council, and the council’s provision of these buildings, that enables it to exist in this form. Across municipalist literature, it is cited as a key example of radical municipalism (Roth et al., 2023). The neighbourhood’s history of mobilisation, aligned with the anti-austerity 15M movement post-2008, saw the council hand over these buildings to the community for social use in 2011, exemplifying an alternative city-citizen-institution relationship that devolves power (Parés et al., 2017). It is not perfect by any means, with many spaces like Can Batlló navigating fraught relationships with a municipality threatening to defund the space. Radical spaces like L’Antiga Massana, a squat and community centre in the heart of the Raval neighbourhood, experience violent evictions because they are a political threat – beating hearts of the barrio and engines for leftist political mobilisation. But this grassroots fight for space is active and ongoing.

Crucially, La Impremta exemplifies a result of this ongoing fight, and the heart of Barcelona’s cultural vibrancy: from the festa majors to the community-run civic centres in every neighbourhood, resources and space have been reclaimed by the people creating a decommodified cultural ecosystem – resources and space which become a proof-of-concept and base to keep the fight alive.

Barcelona’s wave of municipalist organising post financial crisis was energised by a real alliance of inside-outside actors. In contrast, the UK’s response to austerity has been characterised as a “managed municipalism”, a weak, top-down approach driven by local councils rather than grassroots movements (Thompson, 2021; Banks & Oakley, 2024). Spain experienced the financial crisis more sharply than the UK: high levels of unemployment and poverty mobilising huge numbers of people onto the streets to demand change and building dual power outside of the state. The UK’s use of existing political structures has seen a series of failed attempts at decentralisation of power, with council land sold en masse to private developers, rather than handed over to the community.

I have worked in the cultural sector for years now, and I know cultural ecosystems hold serious potential to challenge capitalism from the ground up. Working at the city scale is key to catalysing this change. Cities like my hometown of Bristol, or Glasgow, Liverpool, and Manchester – each with strong socialist tendencies and vibrant cultural identities – are ripe for radical municipalist organising. Where a national-level degrowth strategy feels out of reach, an eco-socialist UK city feels within our grasp.

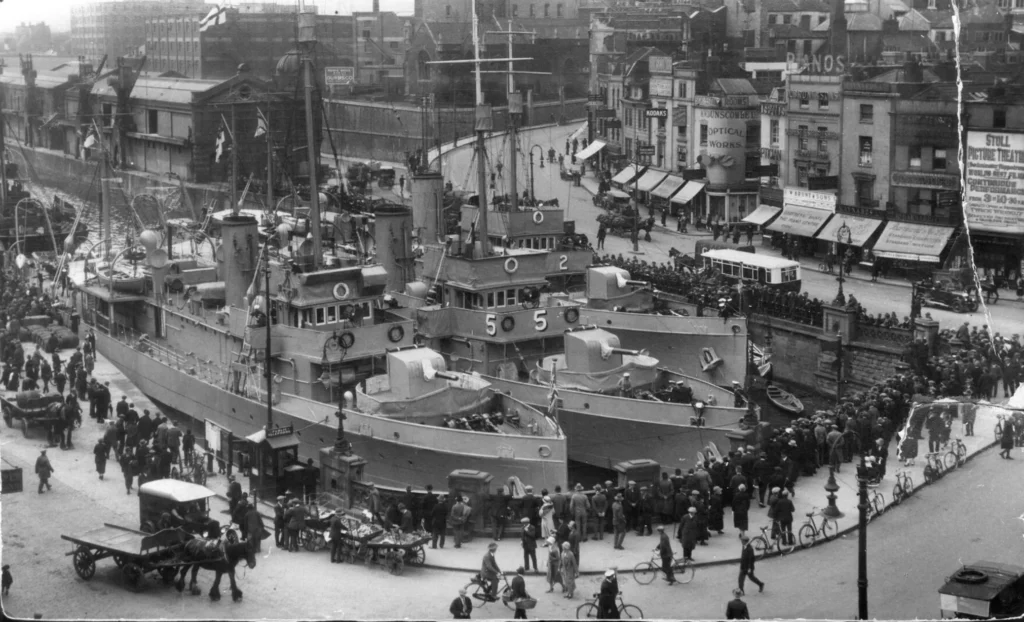

The Irony of ‘The Creative City’

In the UK, we only need to look as far back as the 1980s for policies which harnessed the potential of culture to transform the city. The Greater London Council, known as a ‘social democratic paris commune’ was ‘unimaginable without its cultural policies, alliances and supporters’ (Hatherly, 2020). Manchester’s post industrial revival was driven by a wave of pop culture, transforming post-industrial decline into a gritty cultural hub (New Books in Sociology, 2024). Watershed in Bristol, the cultural cinema and creative technology studio, where I currently work, was city council helped fund their purchase of an abandoned industrial shed, in the hopes a cultural organisation would breathe life back into the derelict, deindustrialised harbour. And it did: 40 years later, the harbourside is the cultural centre of the city.

Images of Bristol’s harbourside in 1926 & 2024

But the story continues. The 1998 Labour government embraced the success of popular culture as a powerful modernising force, branding it “The Creative Industries” (O’Connor, 2024). Seizing on the dot com boom, it wove together culture, technology and business strategy to tackle the rampant unemployment from deindustrialisation. This framing was picked up by UNESCO as a tool for modernisation, entwining cultural policy with economic development doctrines across the world (O’Connor, 2024). Here, culture became segmented from a (semi?) public good into a private consumer economy.

The concept of The Creative City was born, where councils hardened culture into a formal sector, to attract tourism, promote inward investment and shape urban identity. The main beneficiaries were not artists, communities or even businesses – but real estate developers. This so-called ‘investment’ in the arts served to mask a new phase of gentrification, financial restructuring driven by land speculation, as international investment flowed into cities looking for increased capital. Meanwhile, the digital commons was being enclosed, with platform monopolies like Netflix and Spotify seeking to control digital cultural production and consumption through Intellectual Property and algorithmic domination.

The irony is this process of political centralisation has poisoned the fertile soil that first made the cultural industries bloom. Banks & O’Connor argue it was in fact the UKs diverse geographical patchwork of cities and municipalities that first nurtured the vibrant cultural scene (2017). Manchester City Council, once a beacon of working-class creativity, sold off the city centre to developers, eroding the counterculture and diversity of its cultural services.

Since the global financial crisis, local funding for the arts has dropped by 43% (National Campaign for the Arts, 2020), leading to venue closures, funding cuts, and job losses. The result? A fragmented, London-centric, tech-driven cultural sector, where the most commercialised areas – advertising and digital design – are held up as models for community arts.

In the UK, if you want to pursue art as a means to live, you generally have to move to London and sell your soul to pay rent. My best friend’s mum went to art school in the 1980s with the likes of Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst. They all lived in East London squats which no longer exist. The starving artists are actually starving. Unless you have existing capital, your choices are pretty much work for Spotify or face homelessness. The great creative minds of our time either don’t work in the arts or are content creators for oil companies.

But radical municipalism emerges from crisis, which is where we find ourselves (Roth et al, 2023). Indeed, Sandoval argues it is precisely the precariousness and frustrations of bad working conditions that motivates cultural workers to form new alliances of resistance (2018).

Culture: a feminising force?

The simultaneous centralisation of power in the UK and commodification of the arts can be read as a distinctly patriarchal politics: cementing hierarchy, universalism and rationalism. If our municipalist strategies mirror these narrow definitions in avenues towards participation, then it risks reproducing these masculine, western hierarchies of power.

There are different ways of knowing, understanding and being. The arts create space for those to be explored together, to be valued. The UCLG Women report Towards a Global Feminist Municipal Movement asks: “How can we create channels for effective and inclusive participation that incorporate the voices of women and diversity in the construction of public policies?” (2019, 9). I suggest one avenue is taking arts and culture seriously.

Roth and Baird argue that to feminise politics, we must ‘shatter the masculine patterns that reward behavior of competition, urgency, hierarchy and homogeneity, and emphasise the small, the relational, the everyday” (n/a). A feminist municipalist approach could see arts and culture as a tool to embrace the multiplicity of knowledge, actors and relations engaged in civic culture making, and therefore the everyday re-making of the city.

Consider the Land Art Generator Initiative (LAGI), a competition that moves between cities to engage folks with the post-carbon transition. They partner with local municipalities to run competitions, where teams (anyone from artists, to scientists, to school children), submit designs for beautiful, useful, renewable energy infrastructure that responds to local needs. The competition is then judged by a panel of local people. This form of collaborative and creative placemaking engages broad swathes of city-dwellers to come together and imagine a future of civic renewable energy generation: fighting NIMBYISM, creating alliances between private, public and community institutions, and democratising urban planning. It takes advantage of existing urban identity to engage folks in issues they may not otherwise care about.

Two of LAGIs experiments: Beyond the Wave & Solar Orbs

Locating culture in municipalism

Despite this potential, radical municipalist and degrowth literature largely overlooks culture (Banks & Oakley, 2024; Foundational Economy Collective, 2018; Hansen, 2022; Janoo et al., 2021). Roth recently summarised the foundational necessities for “living well” that ought to be the focus of municipalist strategies – yet arts and culture were again absent (2023).

Reset Collective argues for the repositioning of arts and culture within the social foundations of a wellbeing economy (2022). They distinguish between ‘vital’ needs (food, shelter) and ‘enabling’ needs, such as education, health, and culture. Culture, they argue, is not a luxury, but integral to human development, creativity, and the capacity to make meaningful choices (Reset, 2022). The Foundational Economy Collective similarly have come to include ‘social infrastructure such as libraries’ are a crucial part of a foundational economy (Calafati et al. 2023).

Banks’ scathing assessment of Hickel and Kallis’ most popular works exposes how contemporary degrowth is still to develop any credible theory of cultural production (2022). Culture, in their pieces, is reduced to small forms of localised subsistence (Banks, 2022). Do we expect a degrown society to lack public broadcasting, quality journalism, or cultural film? Maybe some degrowthers see organised cultural production as disposable – but aren’t others hoping for a cultural change in how we value ourselves and the world?

And consider the process of transformation, does culture not have a role to play in the shaping of the new values that we so desperately need? In post-2008 Spain, a counter-hegemony against growth had emerged, and Prádanos emphasises the role of culture in not only documenting this transformation, but enabling it to travel further and root deeper. Using cultural theory, he observes how cities like Barcelona blended cultural creativity (film, TV, novels, art) with postgrowth practices (urban gardens, community economies) creating both discursive and practical experimentations challenging the growth hegemony. Indeed, O’Connors argument is that culture as a distinct ‘thing’ emerged as a counter, autonomous space against the economic-rational world, and it’s capture through the evolution of ‘creative industry’ is a depoliticising force (2024). Attending to cultural practices allows us to more deeply understand how counter-hegemonies emerge and sustain.

Beyond La Impremta, Barcelona hosts a vibrant network of alternative cultural spaces that operate at least partially outside capitalist structures on a varying scale of radicalism. The music venue cooperatives like Sala Vol, the communal fiestas at Can Masdeu and the public common partnerships of the Centres Cívics are all spaces which exemplify what Goodman and Bryant (2013) call ‘spaces of intention’, spaces which enable alternative economic geographies to emerge through practice.

It confounds me: even in the UK, we have existing infrastructure, networks and physical buildings, often rooted in local communities, where people voluntarily visit to encounter new ideas. Cultural vibrancy is why people want to live in cities – let us politicise it!

Towards Cultural Municipalist Strategy

To embed cultural strategy within degrowth, starting at the municipal scale makes the most sense. In the UK, local government and local arts were simultaneously strangled at the hands of neoliberalism – so they can be liberated simultaneously.

Creating more equitable and ecological models of cultural production at the city level promotes local economies, generates value that is better retained and shared locally, creating space for civic participation, critical thinking, and community strengthening. On the New Books in Sociology podcast, O’Connor asks: Why, for example, call a collection of live venues a ‘music industry’ when this network of community-based arts and cultural venues could be organised on a far more equitable and sustainable basis through community co-ops?’ (2024).

At the grassroots, the Alter-Cultures project has been mapping Alternative Cultural Places (ACPs) across Europe that operate “within a framework of cooperation”, “attentive to the sorts of futures which they will produce” (Parker et al., 2014a; Bobodilla et al., 2024). These ACPs are scattered and often precarious (operating in meanwhile spaces), but deeply rooted in community, using cultural programming to become hubs for local people with the revitalisation of their neighborhoods. In Barcelona, I posit that there is not just a scattering of single organisations, but actually some form of Alternative Cultural Sector that is thriving at least partially outside of the market.

In the UK, our cultural scene is one of the only things left and right can agree we’re proud of – let us use this! What could a post-growth cultural policy look like? How can we democratise culture and build more expansive models of participation? Whyman has considered how the Preston Model of Community Wealth Building could be adapted to the creative economy (2022), proposing how policy design for the creative sector needs can be more attentive to individual localities to build resilient cultural economies, and in my mind, happier cities.

Cultural municipalism is already being worked out in practice, from the ground up: through the public-common partnerships of Barcelona’s cultural civic centres, of the network of European alternative cultural places mobilising for neighbourhood transitions, in the organisations on the ground continuing to create cultural offerings for their communities despite the increasingly precarious conditions.

These are seeds for transforming urban spaces, for pluralist visions of eco-social transformation. I ask us to attend to them seriously. Word has it La Impremta Col·lectiva have just expanded their studio, so something must be working.

Author: Zoe Rasbash

This text is the adaptation of an essay written as an assignment for R&D’s Master in Political Ecology, Degrowth and Environmental Justice

The opinions expressed in the text do not necessarily reflect those of R&D, but are those of the authors.

References

Banks, M & K. Oakley (2023) ‘Cakes and Ale: the role of culture in the new municipalism’, Cultural Trends.

Banks, M. (2022) The Unanticipated Pleasures of the Future: Degrowth, Post-Growth and Popular Cultural Economies. New formations: a journal of culture, theory and politics. 107 (108), 12-29.

Banks, M., & O’Connor, J. (2017). Inside the whale (and how to get out of there): Looking back on two decades of creative industries research. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 20(6), 637–654.

Calafati, L. Fround, J., Haslam, C., Johal, S. and K. Williams (2023) When nothing works from cost of living to foundational liveability. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Foundational Economy Collective. (2018). Foundational Economy: The Infrastructure of Everyday Life. Manchester University Press.

Hansen, T. (2022). ‘The foundational economy and regional development.’ Regional Studies, 56(6), 1033–1104.

Hatherley, O. (2020). Red metropolis: Socialism and the government of London. Repeater Books.

Janoo, A., Bone Dodds, G., Frank, A., Hafele (Zoe), J., Leth, M., Turner, A., & Weatherhead, M. (2021). Wellbeing Economy Policy Design Guide. Wellbeing economy alliance (WEAll).

National Campaign for the Arts. (2020). New arts index published today | campaign for the arts, June 7th (online 2023)

New Books in Sociology (2024) Justin O’Connor, “Culture is not an Industry”. Podcast.

O’Connor, J. (2024) Culture is Not an Industry: Reclaiming Art and Culture for the Common. Manchester University Press.

Parés M, Ospina S, Subirats J, et al. (2017) Sants: seeking autonomous self-management from below. In: Pares M, Ospina S, Subirats J (eds) Social Innovation and Democratic Leadership: Communities and Social Change from Below. Cheltenham: Elgar, pp. 174–199.

Reset Collective (2022) Art, Culture and the Foundational Economy. University of South Australia.

Roth, L., B. Russel & M. Thompson (2023) ‘Politicising Proximity: Radical municipalism as strategy in crisis’. Urban Studies, 60(11)

Roth, R. & K. Baird (n/a) ‘Municipalism and the Feminization of Politics’, ROAR Magazine (roarmag.org), https://bit.ly/2eIrhbu.

Russell, B. (2019). Beyond the local trap: New municipalism and the rise of the fearless cities. Antipode, 51(3), 989–1010.

Sandoval, M. (2018). ‘From passionate labour to compassionate work: Cultural co-ops, do what you love and social change.’ European Journal of Cultural Studies, 21(2), pp. 113-129

Stefano Harney (2012) ‘Creative Industries Debate: Unfinished business: Labour, Management, and the Creative Industries’, in Mark Hayward (2012) Cultural Studies and Finance Capitalism, London: Routledge.

Thompson, M. (2021). ‘What’s so new about new municipalism?’ Progress in Human Geography, 45(2), 317–342.

UCLGWomen (2019) Towards a Global Feminist Municipal Movement. Durban.