Authors: Filka Sekulova and Giacomo D’Alisa

Citation: D’Alisa, G.; Sekulova, F. (2025, September). Europe beyond growth: The proposal for a Universal Care Income [Policy brief n.2]. Research & Degrowth International. https://degrowth.org/blog/2025/06/17/uci-for-europe/

If European authorities want to put care at the centre, they urgently need to shift the focus of their policies away from extraction, industrial production, and consumption that is fuelling ecological and social breakdown and instead put emphasis on social and environmental care, regeneration, and reproduction. A Universal Care Income, we argue, is a main instrument to move in this direction, and can liberate Europe from the grips of a destructive path of a one-way future consisting only of growth.

The lockdowns we all experienced during Covid19 made us realize the importance of care activities and the need for a social system that puts life at the centre of its political concerns. On the other hand, the lockdowns revealed also how doing so is socially and economically unsustainable for a market system that is still obsessed with growth.

Beyond the EU Care Strategy

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, it was hard for anyone to disagree that care was essential. Commentators and many people welcomed the news in 2022 when the European Commission approved a resolution (COM 2022/440) to launch a Care Strategy for Europe (CSE). The strategy was drafted in a moment of intense debate about the importance of essential workers, the backbone of which were formal and informal carers. However, the CSE did not go far enough.

The CSE was the Commission’s response to the European Parliament’s initiatives motivated by the fact that the European Green Deal lacked a gender perspective and did not pay attention to care (EP 2019/2169). The CSE aims to facilitate access to care, improve the quality of care services and make care more affordable for all European citizens. Moreover, it aspires to improve the working conditions for formal care workers, and to foster an equal gender distribution of caring activities both in the spheres of market and at home to guarantee a fairer work-life balance among all carers. The Commission proposed a number of steps in fulfilling these objectives, in particular in relation to childcare and long-term elderly care.

The European Commission’s approval of the CSE opened a new policy path, as care has historically, largely been hidden and undervalued, creating persistent inequality against carers, the large majority of whom are women, and in particular women from marginalised communities. As the resolution states, 90 per cent of formal care workers are women, and 7.7 million women in Europe are so burdened with unpaid care work that it renders them unable to enter the job market. Researchers at the European Parliamentary Research Service have defined women’s earnings lost due to care work as the “unpaid care penalty” (Fernandes and Navarra, 2022), estimating it at approximately €242 billion per year. Women in Europe dedicate, on average, 2-3 more hours per day to care work than men (EP News, 2022), so up to an extra month and a half every year. Even with the difficulty of calculating exact figures, it is clear that men historically have accumulated ‘a caring debt’ that creates structural gender inequality.

However, the CSE does not offer a clear definition of care. Moreover, its narrow focus on care for children and the ageing European population, implies that only special groups in society need care during specific moments of their life. Thus, it misses the importance of many daily caring activities that sustain both people and the environment.

In this brief, we argue that it is time to both relaunch and reframe this debate and that the European parliamentarians’ call for a Care Deal for Europe (EP 2021/2253) is a great opportunity for institutionalising the right to care as a pillar of the European way of life. To do so, we propose the right to an unconditional income, which we call a Universal Care Income (UCI), that should be granted across Europe to everyone, to recognise all the care work, everyone performs and that sustains life. The UCI unveils and rewards the invisible levels of self, reciprocal, and mutual care that sustain society and ecosystems. It honours all those activities that societies and ecosystems require to be healthy and functioning, from childcare to communal forest management, from disability support to community gardens, from neighbourhood meals to seeds sharing.

It is our contention that a sustainable, equitable, and democratic Europe must be rebuilt on this shared care work. In this light, the proposed council recommendation (COM 2022/0299) on a guaranteed minimum income to raise everyone above the national poverty line is palliative. It has been shown that means-tested social policies (such as a minimum income) enhance social stigma and reproduce economic disparities. We argue that a universal, unconditional income based on recognising care as the essential element that guarantees the well-being of people, their communities and the environment is the most adequate response to Europeans’ multiple crises. It is also widely popular with the public and a winning political proposition. This is the political vision upon which a progressive European Care Deal for Europe can be built to go beyond the narrow approach of the existing care strategy. A UCI makes possible a paradigm shift away from a market-dominated Europe, to a Europe of the people, pursuing care and sufficiency for the well-being of all. A Europe therefore that can prosper without growth.

What do we mean by Care?

Care comprises all daily activities humans perform to ensure their well-being and reproduce a healthy socio-environmental context in which they live and thrive. This includes such diverse activities as looking after children, household chores, companionship to the elderly and the sick, and nourishing relationships to sustain healthy and flourishing social bonds. Care activities also manifest in preparing a common neighbourhood meal, tending to community gardens, cleaning coastal and mountain paths, participating in communal water management and preventive activities against forest fires. While a substantial amount of time goes to caring activities most of this work remains invisible, as only paid work is valued in market economies. Our societies, and many of us, often unconsciously embody patriarchal values that serve capital well and have learned to depreciate care work and shift it mainly to women. Current economic policies – and the market ideology that informs them – help obscure the time dedicated to care. This must change.

Having said that, we do not want to reproduce here a feel-good idea of caring that denies the difficult side of caring that involves drudgery. Caregiving often requires boring repetitive tasks, hard work and sacrifice as in the case of turning a bed-bound person with sores, clearing up hazardous waste in mountain paths or simply thinking again and again, day after day, what to cook for your family members. Giving and receiving care can often be difficult, sometimes even disgusting, and create stress, tension, and resentment. It can also strain relations as when children do not recognise the hard work of a mum absorbed in the daily chores and see it as a lack of love. Caring is a daily life practice that makes the carer as well as the receiver experience interdependence and vulnerability; it is not a painless pleasure free of obligation.

Our growth economies promise the illusion of a life without pain and effort as the apex of human emancipation and progress. The idea of liberation from drudgery remains the ideological backbone of economic growth. However, this fantasy is only available to the privileged few who can outsource the ongoing work, pain, and suffering required to maintain their lifestyles to racialised and impoverished others. The white, educated, rich, European men (and increasingly women) are liberated from the fatigues of life, but only by shifting the costs of their own life to other human and non-human beings that suffer the effects of the exploitation or contamination.

The lack of dignity attributed to care work is linked to the fact that it is women and racialized others that do most of this work. It is not a surprise then that it was radical feminist thinkers that first revealed the importance of care and developed economic theories focused on the reproduction of life, debates enriched and expanded by ecofeminism (Salleh, 2017). It is this feminism thinking that underlies the idea of a UCI, as we will explain further on.

Degrowth for Care

Many feminists have shown that serious engagement with care work is in tension with the formality and detachment that characterise the economic sphere and the growth-led mode of production (Picchio, 2011). Some feminists have highlighted this tension focusing particularly on reproductive care work. The care of a sick person for example follows an illness’s biological time, the care of a pasture the seasons’ cyclical time; the economy instead follows a linear notion of time, seeking to increase productivity and efficiency. Efficiency and productivity underpin hiring and employment, but mothers need to slow down productivity due to the care work newborns and young children, which have their own rhythms indifferent to those of the market economy. As a result people with no care duties are preferred to mothers when it comes to employment.

Time marks a fundamental distinction between (market-based) production and (non-market) social (re)production. In care, time is not allocated based on efficiency but follows the rhythms of human bodies and nature: the sick person must be attended to at the moment of need, the needs of a newborn must be met as they arise, the seed sowed during a specific season. In market activities, time is clocked and follows the logic of maximising profit. Market productivism is thus at odds with the time of care in that it is led by the ups and downs of market supply and demand and uprooted from the ecological times of human and ecosystem regeneration. Furthermore, the time for care work is relational and has a qualitative dimension that cannot be perfectly substituted, e.g. paid babysitting is not the same as parenthood. A paid babysitter working under the pressure of employers is not the same as a parent – and this marketization of care work has a social and a moral cost. It is problematic hence that care activities are increasingly commodified, submitted to the logic of economic growth rather than human choices. This is one more reason why a truly ‘caring Europe’ needs to abandon the obsession with growth.

Degrowth scholars and activists put care at the core of their proposals for transformation to enhance and improve the life conditions of formal and informal carers, re-balance the care burden across genders, and guarantee the ‘freedom to care’ (D’Alisa et al., 2015). A common trap into which multiple care-focused public policies such as the CSE can fall is valorising market arrangements and the freedom to enter the job market as superior to the freedom to care. Growth-driven economies seek solutions that privilege those caring processes that are marketised, industrialised, or even outsourced. Such approaches tend to undo social bonds and even increase overall energy demand. Studies show household care is less energy-intensive than the service care sector. Marketised care activities often involve more commuting (which is very energy intensive), such as when care workers commute to elderly care homes (Eicker and Keil, 2017; D’Alisa and Cattaneo, 2013).

In contrast, degrowth advocates for public policies promoting a ‘care infrastructure’ of proximity – non-commodified care processes, including self-organised mutual support. In this strand, forms of living and producing, such as cohousing and parental collectives that care for their children, form a crucial piece of a degrowth economy.

What policy frameworks such as the CSE also fail to recognise is the crucial role of community-based care services, like voluntary associations of animal care, food banks, collective litter picking on coastal and mountain paths, forest communal management or social solidarity health clinics. Public authorities must urgently guarantee that resources and spaces such as buildings, and public tool libraries are provided for mutual support and local self-organisations that promote care beyond nuclear family kinships. A society of care furthermore requires working time reduction so that people have the time and emotional resources for care and for caring in common.

Along with radical feminist writers (Federici, 2010), degrowth advocates see care and reproduction activities as a collective endeavour. They argue that the concept of caring extends beyond the household and includes many activities that pertain to maintaining the integrity of life such as communal forest management and biodiversity protection (AA. VV. 2019). In the context of the Global South, the work performed by subsistence communities like agro-pastoralists and artisanal fishers in maintenance work for their surrounding ecosystems is caring for the environment.

Why a Universal Care Income?

A Universal Care Income aims to visibilize and recognise the centrality of caring and reproductive work, honouring and giving material support to those who, whether they want to or not, make the material, psychological and emotional effort involved in the reproduction of life day after day. A Universal Care Income is an unconditional and differentiated monetary transfer that all adults living in Europe should receive every month – for example, an amount above the poverty line established as 60 per cent of the median income in a country, i.e. at least €1150 in Germany and €815 in Italy for an individual. This income should be universal and unconditional because the care work done to meet the material needs of human and non-human life is done by everyone and should be compensated by collectively produced wealth. And it should be differentiated because women have historically contributed more to our societies’ care work and should as a matter of principle receive proportionally more than their male peers.

This approach is rooted in the feminist campaign for a wage for domestic work in Italy in the 1970s, which became an international movement. It rejected the assumptions that care activities were ‘naturally’ feminine, and that they did not produce value for society. The women’s movement showed how the exploitation of predominantly male workers at the factory was linked to the exploitation of women ‘in the kitchen’ (so to speak). To ask for a wage for domestic work was to demand from the owners of capital to pay the cost of the hours and hours of unpaid work involved in reproducing the workers upon the work of which the capitalists then made profits.

Today the campaign for UCI goes beyond this early idea of wages for housework, promoting as it does the idea that care and reproductive work are not just in the realm of the household but involving carework in and for communities and ecosystems. Indeed, as argued in the previous section, there is an indissoluble relationship between human beings, communities, and the environment in which they live. What these spheres have in common is precisely the effort to care for human beings and their health, for urban commons, for agricultural land and forests, for the water cycle and climate, and for non-human life and the ecological systems that support it. Capital appropriates the care and reproductive work women and men do to sustain life on Earth, and this is what a UCI aims to redistribute back.

A Universal Care Income for Europe

We have argued above that the proposal of a Universal Care Income should be at the forefront of any European care strategy, reinforcing its principles and acting as the first attempt to challenge growth dependencies in Europe. We maintain that a Care Deal for Europe offers a good opportunity to do so.

The UCI proposal aims to reformulate the Universal Basic Income proposal on a materialist principle, according to which an unconditional income has to be recognised for the work done for caring for human and non-human beings and habitats. We argue that universal income should not be given merely as a safety guarantee to avoid poverty or compensate for unemployment, and should not only be given so that everyone can have the economic independence to participate meaningfully as a citizen in democracy (the two arguments typically marshalled in support of a UBI). It should be given because everyone does care work that contributes to our commonwealth.

As per the practical design and the definition of the level and distribution of a UCI, we suggest, first, to set up it at a minimum amount above the poverty line of each European country, and second, to avoid a top-down implementation by launching a larger-scale public debate concerning implementation questions. This debate should be launched in safe spaces for debate and discussion on various levels to respect the sensibilities and necessities of various peoples and localities. The actual design of UCI should be geographically and place-based, considering the multiple subjectivities and typologies of care work that exist in practice.

Box 1: On the Care Income in Italy

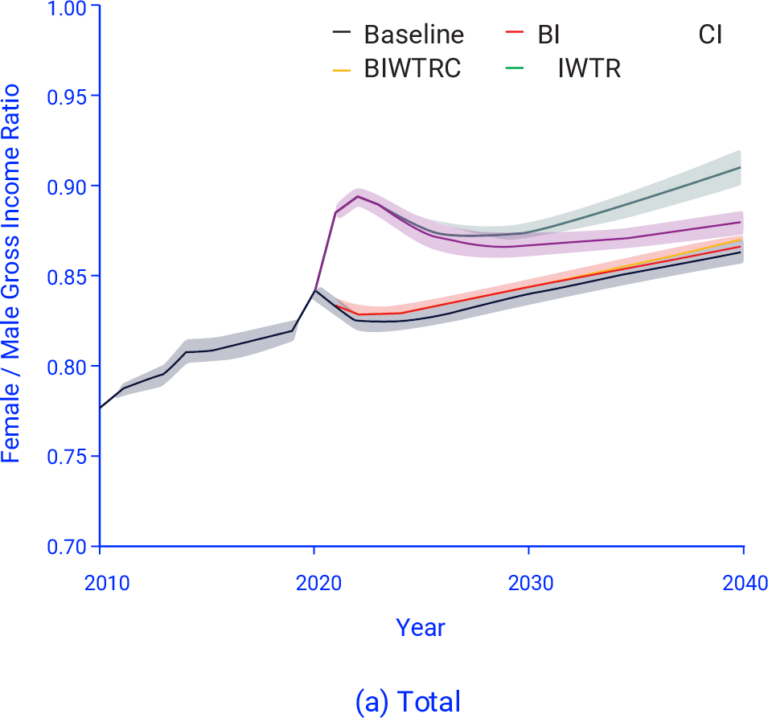

Italian women do reproductive chores and care for more than double the time men do. Fig 1 shows the introduction of a Basic Income, a Care Income and both policies in combination with a Working Time Reduction. The first important result concerns the female and male income levels ratio. It shows that Care Income, and Care Income plus Working Time Reduction, are the best policies to reduce the income gender gap in Italy. In particular, the Care Income plus Working Time Reduction policies increase the ratio to 0.90.

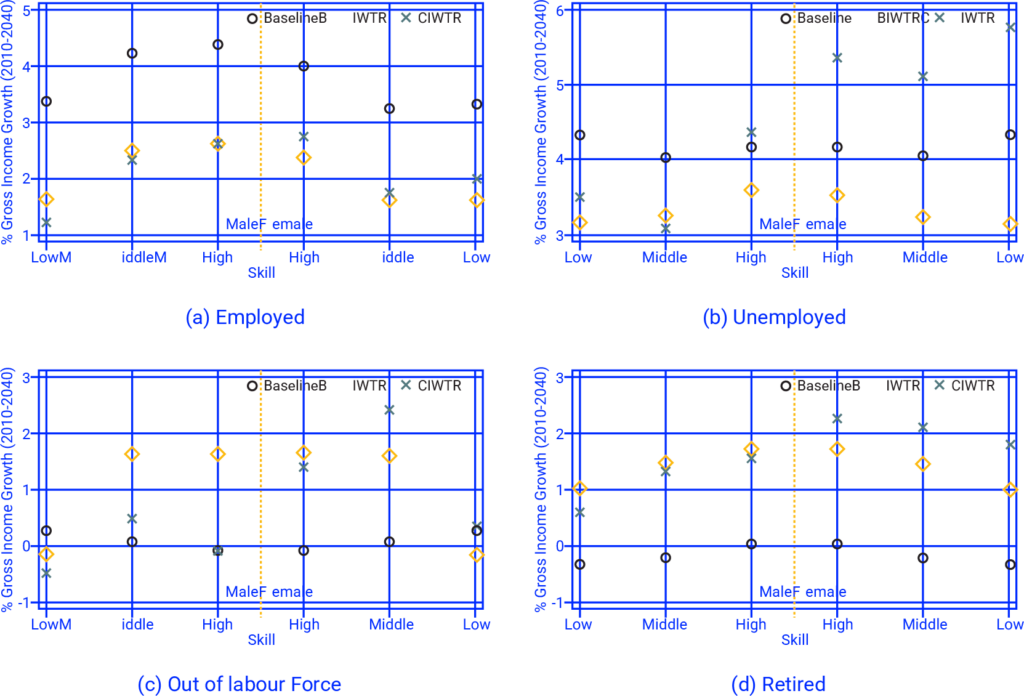

The core equity principle of a universal care income aims to give more to those who contribute more to caring; thus, even more interesting is the result shown in Fig. 2, i.e. a Care Income plus Working Time Reduction policy combination increases the gross income growth rate for unemployed and retired females substantially. Those better off with this combination policy are middle and low skilled women, who normally do more unpaid work overall

For the sake of illustration and as a thought experiment, we empirically estimate the impacts of a UCI in Italy, assuming that women are paid more to compensate for a historical and current gender care debt (Box 1). In this case, UCI can be mainly funded with a progressive increase in taxation for those in higher income brackets. The preliminary results show that those that benefit more from such a policy are those that deserve more as they do on average more care work: middle-aged low-skilled women.

In 2019 civil society launched a progressive proposal for a European Green New Deal. Its proponents included in their programme, which had many features of post-growth, a proposal for a care income. Since then, and in synergy with leading Global Women’s Strike network activists, the proponents of that policy have been promoting a care income worldwide. For the campaigners, putting the focus on care and reproductive work challenges the economic growth model and the care crises it has led to. There are different ideas on how to implement the UCI, and once it becomes part of the political agenda, there will be plenty of room to discuss the actual implementation in diverse localities. For example, some feminist movements in rural areas around the world demand as a care income access to land over cash payments (James and Lopez, 2021).

UCI: Objections and Responses

Here are our responses to six potential issues that the implementation of UCI could raise

Box 2: The B-Mincome pilot Barcelona and its relevance for a potential UCI application in Europe

B-Mincome aimed to test the efficiency and effectiveness of combining economic aid in the form of Municipal Inclusion Support (MIS, i.e. a guaranteed minimum income) with social policies (related to employment, social economy, community participation and housing) in Barcelona’s Eix Besòs area. The MIS was provided to 915 households, randomly selected from the users of municipal social services. The maximum amount a household could get was €1676 per month. The programme included modalities such as the obligation to participate in a range of social policies, or the introduction of means-testing, which reduced the monetary benefit whenever household earnings surpassed a set threshold.

The project is relevant to the question of a UCI in that women comprised the group majority, representing about 2/3 of all beneficiaries. Almost all of them had substantial care-work load, and up to 86 per cent of all participants had children under 18. Almost all participants enjoyed a greater sense of financial and material well-being as a result of receiving the B-MINCOME income and were better able to meet their household’s needs for food, clothing, household essentials, and services. Crucially, many women spent the income on improving their children’s lives, including tuition pay (eg attending semi-private schools), or enrollment in extracurricular activities. Others used the benefit to pay for care services and medications that were otherwise inaccessible to them (due to gaps in public provisioning, for example). For a minority of participants, employment was unlikely to become a realistic possibility or goal, due to poor health or extensive caring responsibilities, especially for single mothers. For these people, B-MINCOME provided a much-needed financial safety net.

The common profile of B-Mincome recipients manifests the higher rates of economic vulnerability among women, all driven by pervasive gender and racial discrimination. As a result of the income some women felt empowered within the family unit, and challenged abusive relationships and existing gender roles. It was mostly women who opted to join the community participation project modality (making 77 percent of all participants), even though the activity was open to all household members associated with the scheme. Through these activities’ women created new or expanded and rebuilt existing social networks. These spaces proved to be fundamental sources of solidarity in moments of social exclusion, gender violence or economic vulnerability. One notable example is the Dones Cosidores collective, established as a result of the project. This community initiative promotes the self-employment of women from various ethnic backgrounds in the field of sewing.

Is there a chance that the UCI could reward more rich women who do little care work than poor men who do lots of care work?

UCI is a policy that recognises the enormous care debt that the vast majority of men have towards women. It addresses women as a collective and not as individuals. Just as with the campaign for recognising the ecological debt owned by Northern countries to the South, the UCI should be framed as a type of reparation for historical injustice towards women. However, high-income women will not receive more than low-income men if the implementation of the UCI is associated with a progressive increase in income taxation, as is the case we presented in Box 1. In this example high-income Italian women will receive more, but they will also be paying much more in taxes than low-income men; low-income men will be better-off after the implementation of UCI.

Thus, to properly address the intersectionality of power and privileges, the UCI needs to be accompanied by other complementary policies such as progressive income taxation, the establishment of income ceilings, as well as working time reduction and job-guarantee schemes, as suggested in the broader degrowth literature.

Doesn’t the UCI reproduce gender binaries?

The UCI, as proposed in this brief, indeed differentiates between gender, in order to address a patriarchal legacy in which women do much more care work. Consequently, they have to be rewarded proportionally. However, the proponents have no intention of discriminating against individuals who identify as transgender or gender non-conforming. We maintain that to avoid reinforcing gender roles and stereotypes, UCI implementation needs to be place-based and democratically designed.

Doesn’t paying women more further cement their role as primary carers? Can’t men say, ‘you are being paid more, so do more’?

Indeed, some feminist writing suggests that a Universal Basic Income (UBI) could confine women to the household, especially when the gains of the marginal income obtained from the labour market are inferior to the monthly UBI benefit (Robeyns, 2010). Others, however, argue that such policy measures could grant women a baseline economic autonomy, fostering their position vis-à-vis the household and the capacity to negotiate the distribution of care-related responsibilities. A universal care income could also give women the time to develop the skills and training they need to earn a better living (Rodriguez, 2016). However, the outcome of such a huge redistributive policy that will change a series of social and economic incentives will not be linear, as it will also depend on a series of cultural traits that vary across geographies. We know from empirical research on pilot implementations, such as the one in Barcelona (see Box 2), that women who receive money are empowered, in most cases, at the family and societal level, and they feel economically safer to break with abusive relationships

How does UCI differ from Universal Basic Income? Isn’t it strategically unwise to start a new parallel campaign to that for a UBI that already has a certain momentum and split efforts in two?

Supporters of different political visions defend a Universal Basic Income (UBI) as a political economy measure to tackle changes in industrial society that lead to increasing unemployment, poverty, etc. On the one hand, there is an Anglo-Saxon liberal tradition, which in most cases supports UBI for instrumental reasons such as keeping poverty or inequalities within a manageable level, in effect seeing the UBI as way to guarantee the stability of capitalist society. On the other hand, there is the European social-republican tradition, which supports UBI because according to them to enjoy freedom and practice democracy effectively each individual must have adequate and secure material conditions. None of these narratives have as the core of their arguments the recognition of the care and reproduction work humans individually and collectively do for their personal, community well-being, and in maintaining a healthy ecosystem. This latter materialist approach that underpins our proposal for a UCI follows the principle “from each according to their ability, to each according to their needs” and is very different from the liberal claims for a UBI. However, it reinforces the argument of social-republicans for material independence. It is not by chance that recently the latter have been more and more open to integrating radical feminists’ claims and criticisms in their research and campaigns. What UCI aspires to do is to make care and material needs core arguments of existing campaigns. One strand of the UBI universe for example which is particularly well aligned with the UCI is the Unconditional Autonomy Allowance (UAA) proposal (Liegey et al. 2013). Inspired by critical political theory, the UAA is indeed meant to redistribute paid and unpaid work while enhancing mutual aid, voluntary and social activity, community care, political activism, and democratic decision-making. And as our UCI proposal, it is to be funded by increasing progressive taxation.

Nonetheless, we should note that many evaluations of current UBI experiments are dominated by rather narrow, market-liberal orientations, focusing largely on the extent to which the measure enhances employability (Verho et al. 2021). From a critical political, feminist and care-based standpoint, and in a context of increasing “in-work poverty”, “bullshit jobs”, and decreasing job meaningfulness, the core achievement of a UBI/UCI shall not be measured by the level of improved employability but by goals such as mental and bodily health, access to education and basic services, including housing, and gender justice. In that respect, many short-term, UBI pilots score reasonably well, as shown in the example in Box 2 from Barcelona.

How do we know that a UCI will have positive social effects?

Just as the ‘wages for housework’ demand was never meant as a stand-alone policy for the movement in the 1970s, recent applications of the UBI demonstrate that cash transfers for women accompanied by policies that strengthen community ties and social bonding have resulted in the establishment of solidarity networks, work-related and in-family emancipation (see Box 2).

How will a UCI be financed? Will it not take public revenue out of other important public services? Wouldn’t it increase debt, especially in a context of degrowth that you advocate here?

In the framework of Care Deal for Europe, we propose an income paid using the long-term EU and Next Generation EU budgets. In general, potential sources for a UCI include progressive income and wealth taxation (including 100 per cent rates above excessively high incomes and wealth levels – what has been called maximum income or wealth institutions). Other possible avenues include taxes on resource extraction, taxing financial transactions, prohibiting tax havens, and tax breaks for large-scale corporations. This could be done more easily if the campaign for UCI was associated with the billionaire campaign to implement fairer taxation. Financed through a substantial change in taxation structure, UCI should not significantly affect public debt.

Giacomo D’Alisa is a political ecological economist whose interdisciplinary, action-oriented research advances sustainability and environmental governance. With over 70 publications, including journal articles, book chapters, and landmark works on degrowth, he has significantly influenced both academia and policy. As Research Director at ICTA-UAB, he explores societal metabolic shifts, environmental justice, and the tensions between growth and degrowth. He also directs the Master’s program in Political Ecology, Environmental Justice, and Degrowth, contributing to the field’s consolidation and transformation.

Filka Sekulova is a senior researcher based in the Department of Economic History, Institutions, Politics and World Economy at the University of Barcelona. Her work is placed at the intersection of (ecological) economics (PhD, MS, BS), psychology (BS), and social sciences, with focus on degrowth, tourism and urban nature, through the perspectives of justice, community organizing and subjective well-being. Her research furthermore explores the barriers and opportunities for post-growth scenarios and policies. Filka is a co-founder of the international think tank Research and Degrowth and a member of the Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice.