By Myfan Jordan.

During Australia’s experience of the coronavirus pandemic, Melbourne/Naarm, was one of the ‘most locked down cities in the world.’ While the economic fallout had firstly impacted younger workers, Australia soon also saw the ‘shecession’ or ‘pink recession’ recognised in other countries. This gendered disadvantage emerging as a result of the crisis articulated the ways in which women were impacted differently than men: with increased vulnerable to unemployment and job precarity as a result of work tenure, and also in the increased burden of unpaid work falling – particularly – on the shoulders of mothers homeschooling younger children and supporting ageing parents and parents-in-law.

With a loss of financial independence and the immense challenges of the changed home environment, it is of little surprise that women in Australia reported higher rates of anxiety than Australian men in 2020 and 2021: not only were they carrying a higher physical (care) burden, but they were also often bearing a higher ‘emotional load’ both at home and in the workplace. Within this context, rates of family violence were also skyrocketing.

The ‘shecession’ narrative had highlighted the particular impacts upon younger mothers, but less was being said about women over 40, a cohort who, in Australia, can face something of a ‘gendered ageing’, typically retiring with half the savings of the average man and for some, experiences of housing insecurity and even homelessness.

To better understand the outcomes of the pandemic for women over 40, I had run a survey across social media asking ‘older’ women about their circumstances and conditions of work during 2020-2021. As expected, survey respondents – many working in education and health, the ‘businesses of care’– reported highly strained and even unsafe conditions of work.

Shockingly, just over 50 percent described workplace cultures and relationships which aligned with Australia’s Fair Work Commission’s definition of workplace bullying. Even more surprising was the fact that this bullying seemed mainly to come from female colleagues.

While women workers were describing highly ‘toxic’ workplaces at the pandemic frontline, outside of paid employment a very different, and also highly gendered, ‘workspace’ was emerging. In the hyper-local digital ‘communities’ of The Good Karma Effect, an Australian ‘buy nothing’ group located on Facebook, women could be seen to be ‘staffing’ a very different care frontline, responding to local need in the provisioning of material items such as newly scarce toilet paper and Rapid Antigen Tests, but also coming together in a ‘hive mind’ collectivism, to offer advice, information and even (virtual) care.

The behaviour I noted operating in three Good Karma Networks (GKNs) across the same time period as the Generation Expendable? study, not only appeared to show women workers displaying very different (economic) behaviours, but, although typically strangers, women working together in relationships typified by conviviality and care: practices aligned with the core tenets of a growing anti-capitalist movement known as ‘degrowth’.

As articulated by Anitra Nelson and Vincent Liegey, in Exploring Degrowth, for a society to function as a degrowth culture it needs to be structured in four key ways:

- Open (re)localisation;

- Conviviality;

- Frugal abundance; and

- ‘Decolonising the growth imaginary’.

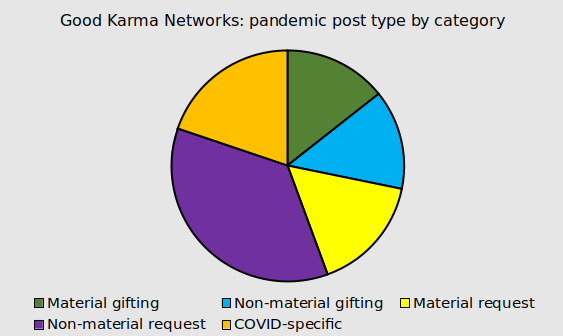

Utilising a theoretic lens of degrowth, I analysed all unique posts on three GKNs1 across 2020 and 2021 to identify if they related to the pandemic. Of 764 posts found, 33.9 percent were virus-specific, showing that these networks functioned as the sort of ‘community noticeboard’ that once used to be associated with local government. The activities taking place across the GKNs also clearly resonated with a degrowth, or post-capitalist model characterised by gift giving.

So-called ‘gift economy’ models are popular with advocates such as Australia’s Terry Leahy, as they propose an alternative mode of social organisation which is circular, and which prioritises humanity’s relationship with the natural world. Gift economies incorporate participatory and collectivist approaches both to decision-making, and to provisioning; i.e., a gift economy still produces goods and services in the same way as growth capitalism, but in ways that are focused on sufficiency rather than excess. That are ‘circular’, non-competitive and which support planetary health.

While more common to pre-modern times, some gift economy practices endure in Indigenous cultural practices. But it is only recently that they have come to be seen as a strategy for moving beyond our globalised and profit-focused ways of being, suggesting an alternative paradigm for living and working together beyond today’s ‘exchange logic’, which rewards self-seeking behaviours over those which might be said to be ‘other-focused’.

With the patterns of behaviour taking place in the GKNs during the pandemic mandated to be positive and also ‘beyond money’, The Gift Highway study analysed whether they might be categorised within gift economy constraints, interrogating every post to understand if they involved:

- Material gift giving;

- Non-material gift giving;

- Material gift requests; and

- Non-material gift requests.

The study found that each of the posts identified successfully fit into categories aligned with gift economy and degrowth models. While the majority were ‘non-material gift requests’ for advice or information, a similar portion was made up of gifting, whether material or non-material items, as Figure 1 shows:

Figure1: GKN Categories by Post Type, 2020-2021

This non-material gifting took a number of forms, but principally it related to the sharing of information around pandemic restrictions and to activities which might be described as building ‘social capital’: the sharing of anecdotes, photos, and other offerings for which the gifter would receive no reward and which contributed to the ‘sense of belonging’ 87 percent of GKN members reported.

Although some men took part in activities, the research found that the micro gift economies identified were, like the paid businesses of care, highly gendered: 85 percent of GKN members were found to be female,2 a finding which gives weight to the feminist gift economy movement focused on a ‘maternal’ gift economy paradigm. While focused on gift-giving as a mode of economic organisation, maternal gift advocates emphasise how ‘matriarchal’ or feminine/female-coded ways of being in the world offer the sort of transformative, ‘degrowth imaginaries’ needed if we are to pivot humanity away from the neo-patriarchal ‘economic fundamentalism’ destroying the planet.

Comparing and contrasting the findings of Generation Expendable? and The Gift Highway, it was clear that women’s behaviour towards one another and to others is not only environmentally specific, but closely related to the economic settings in which caregiving in particular, operates.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Each comprising approximately 5000 individuals living in the same geographic location, yet it seemed mostly unknown to each other in ‘real life’.

2 Based upon perceived gender identity and inclusive of both cisgender and other non-masculine genders.

The opinions expressed in the text do not necessarily reflect those of R&D, but are those of the author.

Myfan Jordan is the Director of Grassroots Research Studio and author of Women’s Work in the Pandemic Economy.